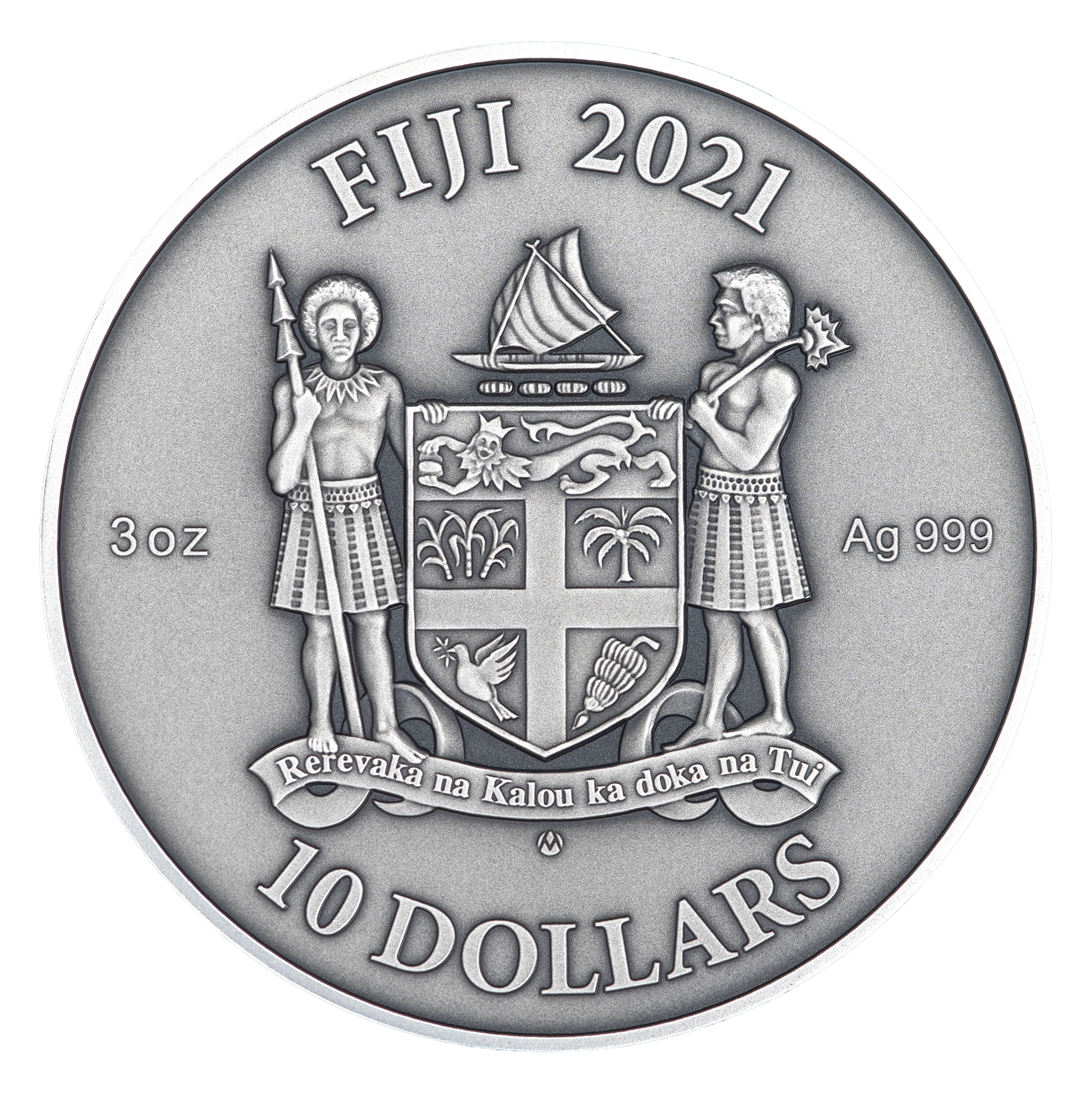

Description

TURKISH ART

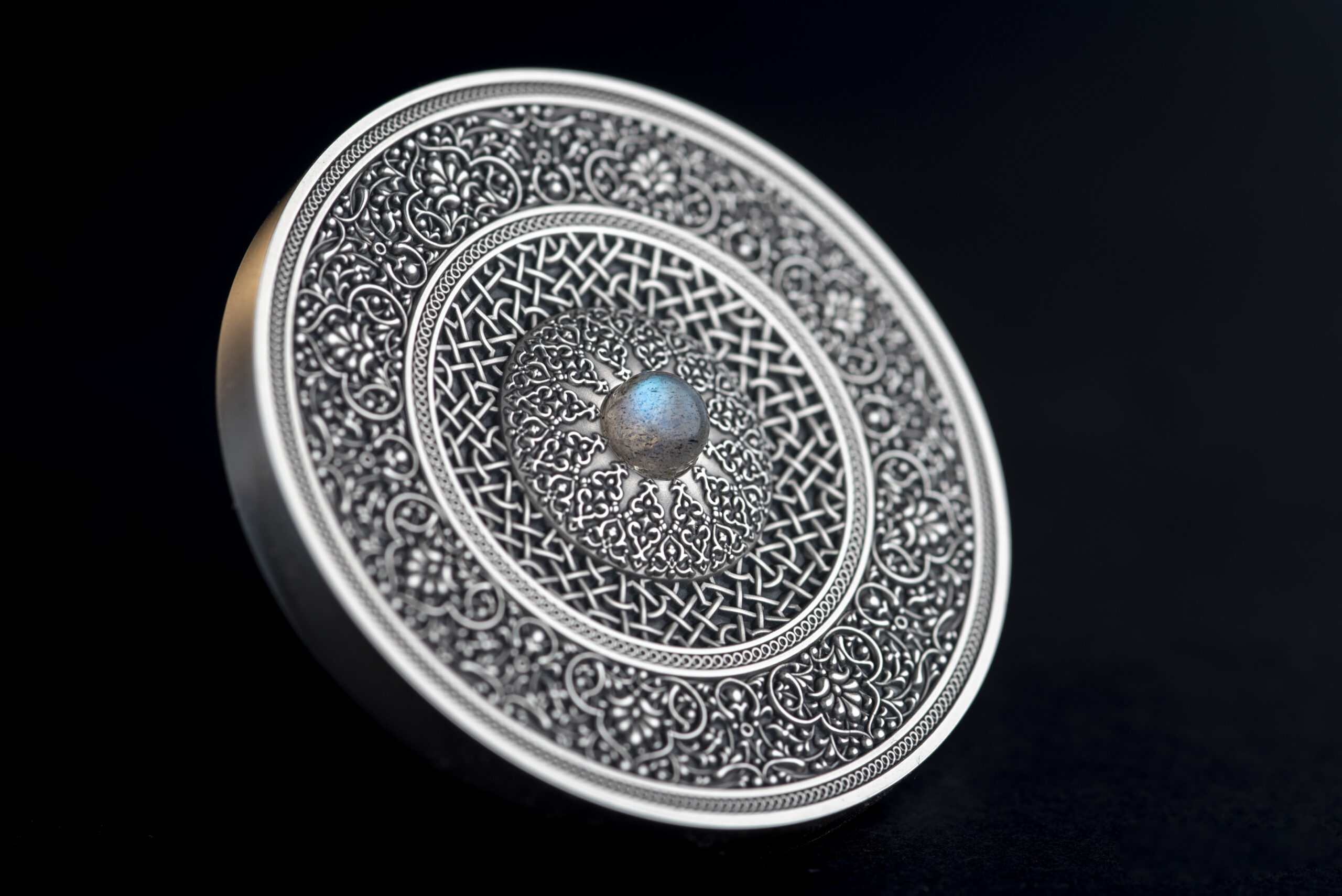

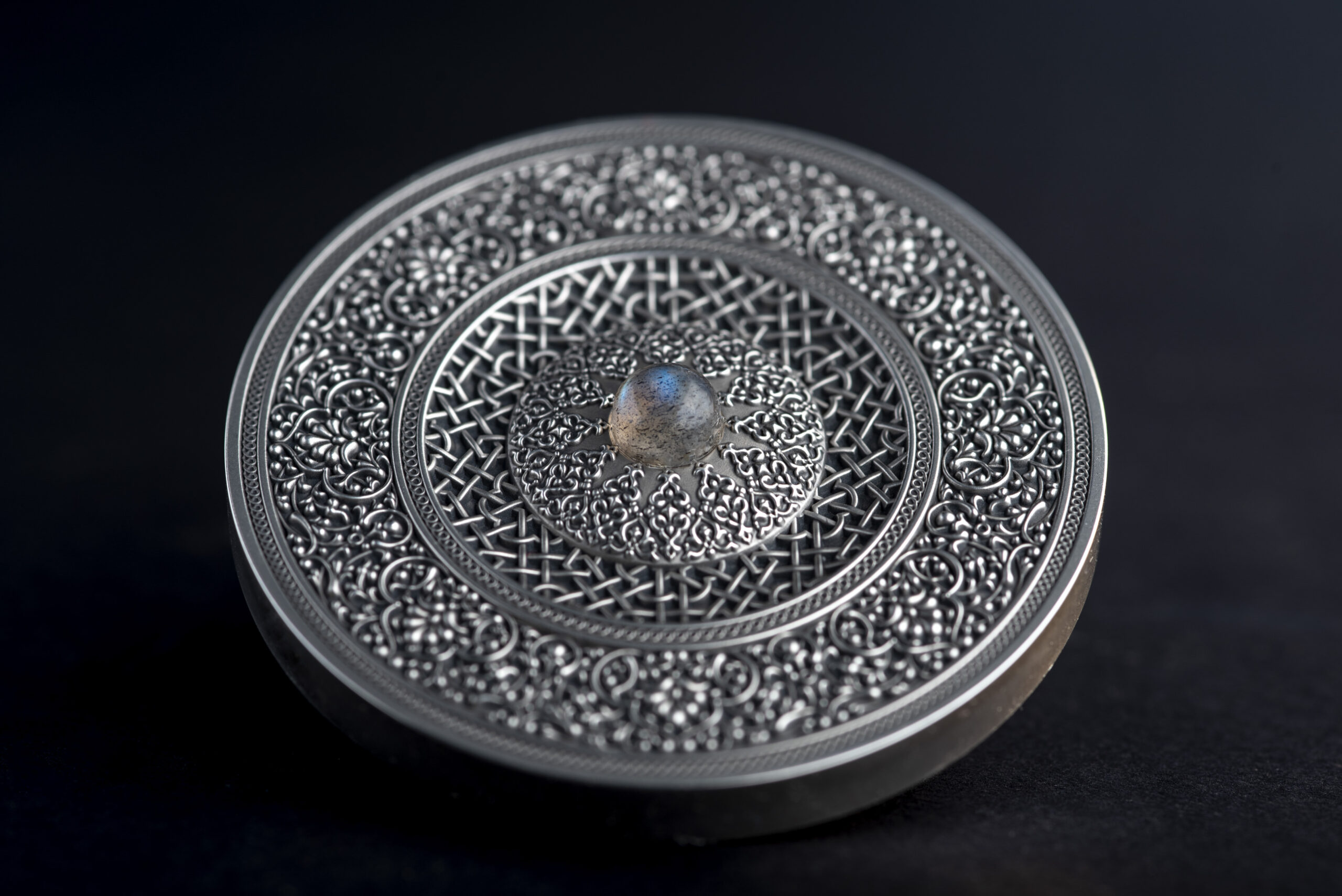

Turkish art refers to all works of visual art originating from the geographical area of what is present day Turkey since the arrival of the Turks in the Middle Ages.Turkey also was the home of much significant art produced by earlier cultures, including the Hittites, Ancient Greeks, and Byzantines. Ottoman art is therefore to the dominant element of Turkish art before the 20th century, although the Seljuks and other earlier Turks also contributed. The 16th and 17th centuries are generally recognized as the finest period for art in the Ottoman Empire, much of it associated with the huge Imperial court. In particular the long reign of Suleiman the Magnificent from 1520 to 1566 brought a combination, rare in any ruling dynasty, of political and military success with strong encouragement of the arts.

The nakkashane, as the palace workshops are now generally known, were evidently very important and productive, but though there is a fair amount of surviving documentation, much remains unclear about how they operated. They operated over many different media, but apparently not including pottery or textiles, with the craftsmen or artists apparently a mixture of slaves, especially Persians, captured in war (at least in the early periods), trained Turks, and foreign specialists. They were not necessarily physically located in the palace, and may have been able to undertake work for other clients as well as the sultan. Many specialities were passed from father to son.

A transition from Islamic artistic traditions under the Ottoman Empire to a more secular, Western orientation has taken place in Turkey. Modern Turkish painters are striving to find their own art forms, free from Western influence. Sculpture is less developed, and public monuments are usually heroic representations of Atatürk and events from the war of independence. Literature is considered the most advanced of contemporary Turkish arts.

MANDALA ART

What is a Mandala?

The meaning of mandala comes from Sanskrit meaning “circle.” It appears in

the Rig Veda as the name of the sections of the work, but is also used in

many other civilizations, religions and philosophies. Even though it may be

dominated by squares or triangles, a mandala has a concentric structure.

Mandalas offer balancing visual elements, symbolizing unity and harmony. The

meanings of individual mandalas is usually different and unique to each

mandala.

The mandala pattern is used in many traditions. In the Americas, Indians

have created medicine wheels and sand mandalas. The circular Aztec calendar

was both a timekeeping device and a religious expression of ancient Aztecs.

In Asia, the Taoist “yin-yang” symbol represents opposition as well as

interdependence. Tibetan mandalas are often highly intricate illustrations

of religious significance that are used for meditation. From Buddhist stupas

to Muslim mosques and Christian cathedrals, the principle of a structure

built around a center is a common theme in architecture.

In common use, mandala has become a generic term for any diagram, chart or

geometric pattern that represents the cosmos metaphysically or symbolically;

a microcosm of the universe.

Representing the universe itself, a mandala is both the microcosm and the

macrocosm, and we are all part of its intricate design. The mandala is more

than an image seen with our eyes; it is an actual moment in time. It can be

can be used as a vehicle to explore art, science, religion and life itself.

Carl Jung said that a mandala symbolizes “a safe refuge of inner

reconciliation and wholeness.” It is “a synthesis of distinctive elements in

a unified scheme representing the basic nature of existence.”